Guest blog by Brian Woolland

discussing his new novel The Invisible Exchange

Working with Border Crossings

I first met Michael Walling in 1996 at a conference at Reading University, Ben Jonson and Theatre, where Michael had been invited to lead a workshop on Jonson’s Poetaster. Since then we have worked together in several different capacities. We’ve established a warm friendship and a working relationship that has been very productive. I readily acknowledge that my collaborations with Border Crossings have all been greatly influential on my writing, but this blog is specifically about the evolution of my new novel, The Invisible Exchange (published at the end of July 2022), and how working with Border Crossings has been so significant in its development.

I’ve written three plays for Border Crossings – Double Tongue (2001/2002), This Flesh is Mine (2014) , and When Nobody Returns (2016). I also took an active part in The Promised Land project. The development of each of the plays involved extensive research, workshops and discussions – with Michael, the casts and those with interests in the subject matter. The processes of preparing and writing a play might seem very different from writing a historical novel set in the early C17th, but there are surprising similarities.

The historical background to the novel

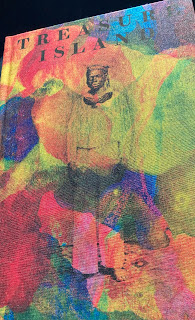

|

Frances Howard

|

I first became aware of the story of Frances Howard at about the time that Michael and I first met, when I was a lecturer in theatre at Reading University, and much of my work was focused on early C17th theatre. Contemporary events are often referred to in plays of the period. Aspects of Frances Howard’s extraordinary story are alluded to (albeit thinly disguised) in several plays of the period – perhaps most notably those by Ben Jonson, Thomas Middleton and John Webster. Frances Howard was the daughter of Lord Thomas Howard (Earl of Suffolk). In 1604, at the age of fourteen, she was married to Robert Devereux, 3rd Earl of Essex, who was about six months younger than her. The arranged marriage was intended as a political reconciliation between two immensely powerful families. But the marriage was a disaster. Despite his inability (or unwillingness) to consummate the marriage, Essex became intensely jealous of his wife’s popularity at court, and he insisted she leave London and live at Chartley Manor, his moated mansion house in Staffordshire, where Mary Queen of Scots had been held under house arrest immediately prior to her execution. Frances was there for much of the summer and early autumn of 1611.

On 25th September 1613, her marriage was annulled, and thus she became the first Englishwoman to successfully seek her own divorce – but in a deeply misogynist society she paid a terrible price for her fierce intelligence and independent spirit. Two years after marrying her second husband (Viscount Rochester, formerly Robert Carr) she was accused of murdering Sir Thomas Overbury, who had been imprisoned in the Tower of London on a charge of treason. No evidence was produced at her trial which would stand up in a modern law court, and she was not permitted to defend herself despite having to suffer a stream of damning accusations which amounted to little more than malicious libels. The central argument against her was that she was a ‘creature of the deed’ – meaning that if she dared to initiate her own divorce proceedings, then she must be capable of murder.

The story fascinated me for numerous reasons. Frances’s trial revealed so much – not only about misogyny, but also about corruption at the heart of the Stuart court. I was intrigued by the parallels with our so-called ‘modern’ times. Frances was treated as a femme fatale who was branded by her prosecutor as so evil that she wasn’t allowed to speak in her own defence at her trial. The murder of Sir Thomas Overbury resulted in the execution of four ‘bit-part players’ and the imprisonment Frances and Rochester (by then they had become Earl and Countess of Somerset). Frances pleaded guilty to the charge of murder, though it seems likely that this was a kind of plea-bargaining because by then she and Rochester had a daughter, and the family was allowed to live together in relative comfort in the Tower. That in itself is very strange, for if they had been genuinely guilty of murder they would almost certainly have been executed. After seven years in the Tower, however, they were pardoned by King James, and released.

All of this intrigued me, although I had no idea how I would write a novel about it – until I came across rumours in contemporary pamphlets which referred to persistent rumours that Frances was seen in and around London during the period when Essex kept her under virtual house arrest at his mouldering manor house in Staffordshire. There is no evidence in the historical records that she was spirited out of Chartley, but for me it provoked ‘the big suppose’ that gave me starting point for the novel that became The Invisible Exchange.

Points of view

When Michael and I first met, we naturally talked about shared interests. One of those interests was the theatre of Ben Jonson. Jonson was a complex man who wore his contradictions proudly. In some ways he was a conservative. In his poetry he often champions the stability of an old order, but in his plays he positions those from the underclasses and in the social margins at the very centre, he gives them real agency and invests them with wit and energy that far surpasses their social ‘superiors’. As Peter Barnes (who also participated in that conference) put it: 'Jonson never writes about Kings and Queens, that whole moth-eaten hierarchy of privilege and incompetence, but about people like us, working people who work to live...' (1). It was exactly those qualities that appealed so much to me and which also attracted me to the work of Border Crossings, for one of the defining characteristics of the company’s work is the desire to give voice to those who have been socially, politically, historically and geographically marginalised.

Although Frances Howard was an aristocrat (her family was said to be one of the wealthiest in the Kingdom) she has been marginalised by the Jacobean ‘justice’ system and by historians until very recently. I was interested in the way the story revealed the ways that institutionalised misogyny vilified and silenced her. (2) I started on a version in which the story was told predominantly from her point of view, but I found that didn’t enable me to reveal the mechanisms of that misogyny. I continued working on the novel in various different versions over many years, setting it aside for long periods while I worked on other projects, then returning to it. It was there in the background while I worked with Border Crossings on the two Homer plays and on The Promised Land project.

The workshops with Zoukak Theatre in Beirut (3) had a profound impact on me, and on the development of This Flesh is Mine. I took a series of early drafts of scenes which I imagined would form the spine of the finished play. As in The Iliad itself, these episodes were predominantly from the point of view of Achilles. In response to those workshops the play changed in many ways. As I wrote in an earlier blog:

Perhaps the most important single change in my thinking was to realise the importance of Briseis in the narrative. She is only mentioned twice in The Iliad – in the opening pages and the final pages. The … ‘spine’ of scenes referred to above… now becomes what is effectively Act One – which is set in an ancient world. The characters – Achilles, Agamemnon, Briseis, Hecuba, amongst others – continue through to the second act; which is set in a modern world. In Act One, the modern bleeds into the classical; and in Act Two, the classical bleeds through into the modern. And what starts with Achilles as the central character … gradually shifts focus to Briseis and Hecuba. (4)

|

| This Flesh is Mine |

The conversations with Michael and with the workshop participants at Zoukak (and at a later stage with the Palestinian actors of

Ashtar Theatre) resulted in major changes to the play that became

This Flesh is Mine. On a more sub-conscious level, these conversations affected my thinking about the historical novel (which was gently simmering on a back burner at that time). When I returned to working on it, I knew that I needed to use a different narrative voice, to find a central character who would have the potential to engage a reader through an unusual perspective – in short, an equivalent to Briseis. He or she would be an outsider, who had access to the corridors of power, who knew the world of the Jacobean court but was not part of it. I wrote several chapters from the point of view of a gentleman usher. I wrote chapters through the eyes of Frances’s personal maid. But found that their social roles made them too passive. They could observe, but not affect what they saw. I needed a character who could exert more agency.

And so, after several false starts, I experimented with telling the story through the eyes of a character who had been a relatively minor player in earlier drafts – Matthew Edgworth, a rogue and a fixer who’s employed by Rochester to enable his affair with Frances. Matthew is a fictional character, although the world he inhabits is thoroughly researched. In the novel he talks briefly about how much he learnt from going to the theatres from an early age. I didn’t consciously create him in the tradition of those Jacobean malcontents who breathe such wit and dark energy into some of the plays of the period – for example, Edmund in King Lear, Bosola in The Duchess of Malfi, Flamineo in The White Devil (both by John Webster), De Flores in Middleton and Rowley’s The Changeling – but that is what Matthew became, a cross between a malcontent servant determined to break the glass ceiling and a Jonsonian trickster. As Matthew puts it (for the novel is written in his voice), “I’ve never had my master’s looks but I’m no fuckwit. If a smockfaced page can rise to favour, I too can make my way in the world, even if my scarred face will never decorate the pillows of the powerful.” Matthew’s story began to develop a life of its own. The overweening ambition and ruthless cunning that he’s inherited from his dramatic ancestors drives the novel’s plot, but it also serves an additional function, giving him access to the palaces and grand houses of the aristocracy, as well as the murky underworld of Jacobean London – the taverns, the gambling dens, the brothels and the prisons.

When Nobody Returns – seeing from inside and outside

Although I cannot identify a specific moment during the development process for When Nobody Returns which is an equivalent to those workshops with Zoukak, it’s clear to me with hindsight that the discussions with Michael and the cast, and with the workshop participants (5) led me to write a play in which each of the three central characters, Telémakhos, Penelope and Odysseus, is in some ways an ‘outsider’. Telémakhos and Penelope have been forced to become outsiders in their own homeland because of the occupation. At the start of the play (and of The Odyssey) Telémakhos is twenty years old, the same age his father was when he left home to fight in the Trojan War. He hears rumours about his father, and is determined to discover the truth about them, so he leaves for mainland Greece to seek out those who knew his father. His identity is bound up with knowing his father, living up to (or living down) the stories he hears about him. When he reaches the court of Menelaus he becomes a stranger in a strange land, and on returning to Ithaka and finally meeting his father, his sense of self, of what is right, of what is necessary to rid the island of the occupation, is profoundly challenged.

|

| When Nobody Returns |

The main character in When Nobody Returns may be Odysseus, but the point of view in the play shifts. We see the occupation of Ithaka through the eyes of Penelope; and, as in Homer, it is Telémakhos’s curiosity that takes him to the court of Menelaus, where he hears stories about his father. Penelope has become an outsider in her own home, and her attempts to subvert the occupation are important – for what they reveal about her strength, and also for what they reveal about the inhumanity of the occupation. Telémakhos is an outsider in search of the ‘inside’ information that will lead him to his father. And his father, Odysseus, is a stranger to himself, struggling to come to terms with his own identity as he battles those demons that still haunt him after his experiences of war. And throughout the play there is a continuing interrogation of what we mean by home – what draws us back, what keeps us away, and what happens when the solid certainties of home become unstable, whether through occupation or trauma.

Thematically, a number of similar concerns run through The Invisible Exchange. Matthew Edgworth is both an insider and an outsider. Like Odysseus, he’s a shape shifter, a master of disguise who can adapt to different social situations; and like Odysseus, he’s renowned for his cunning, but he is a dangerous man; a danger to others, and ultimately a danger to himself. But there are also echoes of Telémakhos in his characterisation. For all his roguish cunning, there’s a softer side to Matthew than the character he seeks to present us with. As Kate (Frances Howard’s maid) says to him: ‘You are not so heartless as you pretend.’ And the relentless curiosity he shares with Telémakhos makes him open to the different cultures he encounters. He’s successful as a trickster because he can use the desires of those he’s gulling against them. But to do that successfully, he has to be an attentive listener and to think as others think As he says about working for Rochester, ‘… the trick of it was to plant the seed, give it time to grow, then be astonished at his razor wit as the seed sprouted and the plan became his own.’ In the course of the novel, he meets four strong, powerful women, each from very different backgrounds: Frances Howard, the aristocrat; Alice, a woman he finds working as a prostitute; Kate, Frances’s personal maid; and Hannah, a cunning woman. He assumes he can manipulate and exploit them. But each of them challenges his certainties. Despite thinking he can work for Frances as well as Rochester, that he can play them off against each other to his own ends, he realises that Frances is ‘as ruthless as any of the men in her family, and far shrewder than her lover or her husband.’ I’ll leave the reader to discover how Matthew is confounded by his dealings with Kate and Hannah. It is, however, important to mention Alice, for her character evolved in response to our experiences of The Promised Land project. Matthew first meets her when he visits a brothel, ‘the House at the Sign of the Vixen in Petticoat Lane. I’d come to see Diego, the broker for the house. He owed me favours.’ Matthew sees a common prostitute. Alice, however, is not what she seems. As she herself says, ‘No matter where you found me, I’m no whore. And I cannot be bought.’ She refuses the easy labels that society assigns to her, and gradually we (and Matthew) discover her history. The large-scale settlement of Huguenot refugees in Spitalfields did not take place until the 1680s. But the persecution of Protestants in France and Holland had started long before that. This novel speculates that some families, such as Alice’s, had already tried to settle in the area in the early seventeenth century. By the time we were working on The Promised Land project, I had begun to make real progress with The Invisible Exchange. But Alice was still a walk-on role. I had always thought of her as intelligent and spirited, but hearing so many stories of real refugees, told with such passion and dignity, I felt compelled to allow Alice a far more significant role in the novel than I had originally conceived. It was the role her story demanded. I conceived of The Invisible Exchange as the first novel in a trilogy. I am currently working on the second, Creatures of the Deed. The character of Alice has now become so important and her story so urgent that the third novel in the trilogy (provisionally entitled The Turbulent Surge) has Alice as the central character and narrator. She will get to tell her story.

Work that changes us

One of the things I have most enjoyed about working with Michael and with Border Crossings has been the sense that the work we’re doing may be for others, but it changes us. The process itself is always a discovery. Crossing borders – our own as well as those imposed by others (political / social / cultural) – is at the heart of the work. I have been challenged and my work has been enriched by the collaborations. In The Invisible Exchange, Matthew’s attitudes and assumptions are of his time and his place, but he sees possibilities, and he acts on them:

‘I liked the way Hannah thought. Stay alert to possibilities. When Lady Luck smiles, be sure to smile back and accept what she’s offering with good grace, for she’ll turn on you and damn you quick as blink. You see a possibility. You make it happen.’

The Invisible Exchange is now available in paperback from all bookshops, and in all e-book formats from 28th July.

1 Extract from the text of Peter Barnes’s illustrated lecture on Jonsonian comedy at the Reading Conference on 10th January 1996.

2 David Lindley’s excellent book, The Trials of Frances Howard (Routledge 1993), offers a closely argued and rigorously research analysis of this institutionalised misogyny.

3 The workshops in Beirut were funded by The British Council. The original intention had been for Border Crossings to co-produce with Zoukak. For logistical reasons that proved impossible.

4 Michael has also written a blog about the process of working with Zoukak.

5 The key workshops that informed the development of the play took place in Salisbury with young people from military families, and with Palestinians at a summer school held in Jordan under the auspices of the Al Qattan organisation.