|

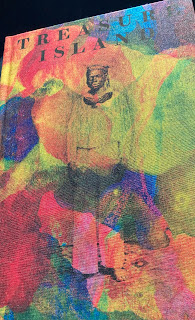

| Treasure Island in Shiraz's version |

I'm not sure whether I've read Treasure Island before. I certainly feel as if I have: it was a staple of BBC Sunday evening family viewing in the 1970s, and several films. I remember it being an inspiration for something I wrote at primary school, and I recall discussing Ben Gunn's mental state with my father while we looked at an old edition in his sister's house in Leeds. It's one of those books that is so embedded in the culture that you feel you've read it, even if you haven't. Well, now I definitely have read it - and it's not quite the book I believed it was.

The reason I think this is that the copy I read was in a beautiful new edition by Four Corners Books, issued as part of their Familiars series. They take a classic text, and they commission an artist to work in dialogue with it. In the case of Treasure Island, the artist was our friend Shiraz Bayjoo, the Mauritian artist who designed THE GREAT EXPERIMENT. He tells me that, when Four Corners approached him, his first instinct was to turn the job down, because he didn't really like the novel. That, the editors told him, was exactly the point. They didn't want him to illustrate the novel so much as deconstruct it, engage with it, expose it and play with it. And that is exactly what he has done.

If you saw THE GREAT EXPERIMENT, you'll remember how Shiraz works with archival imagery to create vibrant and provocative interactions between past and present. Applied to Treasure Island, the effect of this approach is to shock the reader into a realisation of how deeply Stevenson's text is anchored in a context of British imperialism, slavery and racism. Shiraz's archive imagery reveals that the Admiral Benbow Inn is named after the naval commander who protected British plantations in the Caribbean. When Jim Hawkins goes to Bristol, the choice of pictures reveals this as the city of Edward Colston. When the text mentions how three pirates hoped for a reward for their deeds, Shiraz adds an image of St. Louis Cathedral, Mauritius.

|

| Joseph Johnson, in Shiraz Bayjoo's illustration |

Above all, Shiraz's choice and placing of imagery brings out layers of racial politics in the novel that I would never have suspected might exist from the BBC teatime or Disney versions. This engraving of the black sailor turned street singer Joseph Johnson is placed at the beginning of the novel, in the section introducing the old sea captain Billy Bones. It gives a whole new meaning to the description of him as "a tall, strong, heavy, nut-brown man". Nor is Billy the only "pirate" who could be a black man. Israel Hands is described as "that brandy-faced rascal", and Morgan as "the old mahogany-faced seaman". When Jim Hawkins first encounters Ben Gunn, he comments "I could now see that he was a white man like myself", suggesting that this was not his initial expectation. Most strikingly of all, Long John Silver's wife, who never appears but who is clearly central to his plotting, looking after his considerable fortune while he is at sea, is called "his Negress". When Squire Trelawney writes to Dr. Livesey about Silver, he remarks: "He leaves his wife to manage the inn; and as she is a woman of colour, a pair of old bachelors like you and I may be excused for guessing it is the wife, quite as much as the health, that sends him back to roving."

Trelawney's obvious racism and sexism sits very uneasily with a contemporary reading, but it highlights the novel's extraordinary approach to morality, and its political basis. Everyone in the novel is trying to obtain the treasure that the pirate Captain Flint buried on the island: it's just that some are seen as "good" in doing so, and others as "bad". The "good" characters just happen to be white and British. If we understand that the "bad" characters are lower class in origin or black, then it becomes clear that the perceived ethical difference is simply a manifestation of rank. White British men are entitled to wealth because of who they are: black men and women, and people born into poverty, are considered evil if they try to obtain the same wealth by the same means.

This blog post was written in the aftermath of the Queen's Platinum Jubilee celebrations, and the day after Boris Johnson survived a vote of confidence by Tory MPs.